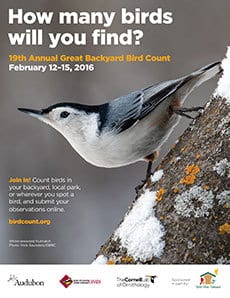

With the El Niño weather phenomenon warming Pacific waters and contributing to record-warm temperatures this winter, participants in the 2016 Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC) may be in for a few surprises. The 19th annual GBBC starts tomorrow, February 12, and continues through Monday, February 15. Information gathered and reported online at birdcount.org will help scientists track changes in bird distribution, some of which may be traced to El Niño storms, unusual weather patterns, and accelerating climate change.

“The most recent big El Niño took place during the winter of 1997-98,” says the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Marshall Iliff, a leader of the eBird program, which collects worldwide bird counts year-round and also provides the backbone for the GBBC. “The GBBC was launched in February 1998 and was pretty small at first. This will be the first time we’ll have tens of thousands of people doing the count during a whopper El Niño.”

“We’ve seen huge storms in western North America plus an unusually mild and snow-free winter in much of the Northeast,” notes Audubon chief scientist Gary Langham. This means some species are turning up in unexpected places. For example, a Bullock ’s oriole was seen in recent weeks in Pakenham, near Ottawa. GBBC organizers are curious to see what other odd sightings might be recorded by volunteers during this year’s count.

Though rarities and out-of-range species are exciting, it’s important to keep track of more common birds, too. Many species around the world are in steep decline and tracking changes in distribution and numbers over time is vital to determine if conservation measures are needed. Everyone can play a role. The count provides insight into the dynamics of bird populations and helps to answer questions such as:

- How how big is this year’s movement of northern species such as pine siskins, purple finches, common redpolls and bohemian waxwings into the Kawarthas?

- What kinds of differences in bird diversity are apparent in cities versus suburban and rural areas?

- Are any new birds undergoing worrisome declines that point to the need for conservation attention? Any readers who attended the screening of “The Messenger” at the recent Reframe Film Festival in Peterborough will be aware of the many threats faced by songbirds. Increasing the database by taking part in the GBBC is one tangible way that you can help them.

How to participate

A joint project of Bird Studies Canada and Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Audubon in the U.S., the GBBC is open to anyone of any skill level and welcomes bird observations from any location, including backyards, cottages, parks and urban landscapes. The four-day count typically receives sightings from tens of thousands of people reporting more than 600 bird species in Canada and the United States alone. Anyone visiting the GBBC website will also be able to see bird observations pouring in from other parts of the world. Just follow these simple steps.

1. Register for the count or use your existing login name and password. If you have never participated in the GBBC, you’ll need to create a new account. If you don’t have a computer, try to arrange for someone else to enter the data for you.

2. Count birds for at least 15 minutes – or longer if you wish – on one or more of the days. Count birds in as many places and on as many days as you like—one day, two days, or all four days. Submit a separate checklist for each new day, for each new location, or for the same location if you counted at a different time of day. Estimate the number of individuals of each species you saw during your count period.

3. Enter your results on the GBBC website by clicking “Submit Observations” on the home page. Alternatively, you can download the free eBird Mobile app to enter data on a mobile device. If you already participate in the eBird citizen-science project, just use eBird to submit your sightings. Your checklists will count toward the GBBC. Online maps and lists are continually updated throughout the count, making it easy to see how your sightings compare to what is being seen elsewhere in the city, province, country or world.

4. You can also enter the photo contest, win prizes, and share your experiences on the Facebook and Twitter social networks. To follow the reporting in real time on Twitter, use the #GBBC hashtag.

5. The GBBC website also has special materials for children. In fact, you may want to go one-step further and take part in the count with your children or grandchildren. This would be a great way to celebrate Family Day, which is on February 15.

2015 GBBC

In last year’s GBBC, participants from more than 100 countries submitted a record 147,265 bird checklists and broke the previous count record for the number of species. The 5,090 species reported represent nearly half the possible bird species in the world. As for Canada, 241 species were recorded on more than 10,000 checklists. In Peterborough County, 62 observers submitted 224 checklists, which included some less-common species like the trumpeter swan, evening grosbeak, brown-headed cowbird, Carolina wren and red-bellied woodpecker. It is expected that participation this year will eclipse the 2015 numbers. The weather last February was bitterly cold and tough on both birders and birds.

Don’t be shy

Don’t feel intimidated if you’ve never taken part in the GBBC before or doubt your ability to identify birds. In a survey of participants who took part in 2009, more than 36% were doing so for the first time. Only about a third of participants considered their skill at identifying birds to be “advanced or expert.” However, the majority of respondents said that they enjoy watching birds every day and that by doing so they experience a satisfying connection with nature.

Please consider taking part this year, and encourage your family, friends and neighbours to do so as well. Remember, too, that the Great Backyard Bird Count is a great way for kids to participate in a real scientific study as junior citizen scientists and, who knows, begin to develop a life-long interest in the natural world. We need as many new conservationists as we can get.

Citizen science

The Great Backyard Bird Count is just one project in the rapidly expanding field of “citizen science.” This is scientific research conducted in whole or in part by volunteers, usually with no formal background or experience in the area. Citizen science projects make you look more closely and really pay attention to all that surrounds you. Participants can become the “eyes” and “ears” for professional scientists. Increasingly, many areas of science such as conservation biology have a huge need for citizen scientists in order to properly do their work. Dentists are becoming lepidopterists, plumbers are contributing to our knowledge of lizards and grade three students are tracking monarch butterflies. In the process, people feel more engaged with the scientific process and with the natural world in general. Participants also develop a new sense of what a specific plant or animal is going through as human impact on the environment increases.

Clouds on horizon?

A post-GBBC survey done by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology after last year’s count found that only 15 percent of participants in the GBBC are less than 50 years of age. This is troublesome, since it is another sign that engagement with nature is far less common among younger people. Participation on the part of non-whites was also extremely low at less than 10 percent. In a continent as multi-cultural as North America, we have to be concerned that more people who identify as non-white don’t take part. On a more positive note, most participants were very happy with their GBBC experience, and found counting birds and submitting and exploring data to be enjoyable. Ninety percent said that they were very likely to participate again.

As parents and grandparents, we need to do more to help young people develop an interest in nature. It is also important that we do what we can to reach out to new Canadians and share our love for the natural world. If we don’t, it’s hard to imagine who tomorrow’s conservationists will be. Who will speak out for threatened species and habitats, when the formative experiences that make for caring stewards are no longer part of so many people’s experience?

It’s essential for the future of conservation to cultivate an interest in nature in young people – Drew Monkman