| Genealogy has never been more popular. It’s wonderful to be able to trace our roots back in time and to see how the choices and life experiences of our ancestors have impacted our own lives. Both of my parents have done a great deal of research on their respective sides of the family and organized the information and photographs in book form for the rest of the family to enjoy. My father has been able to trace the Monkman lineage back seven generations to the 1700s in Yorkshire, England.Today I’d like you to join me as I continue my father’s work, only this time going back an additional 185 million generations! The science involved in this ambitious undertaking comes courtesy of

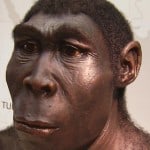

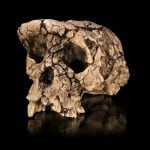

Charles Darwin, the father of the theory of evolution and whose 205th birthday was yesterday. The other tool we’ll be using is a thought experiment described by Richard Dawkins in his 2011 book, “The Magic of Reality”. In this beautifully illustrated volume for younger readers, Dawkins separates “too-little-known facts from too-frequently-believed fictions” about the Universe and nature. He writes: “The magic of reality is – quite simply -wonderful. Wonderful and real. Wonderful because it’s real.” To do this experiment, I’m going to start with a photograph of myself. Next, I’ll place a picture of my father, Cy, on top. I’ll do the same with pictures of my grandfather, Gordon, my great-grandfather, Edwin, my great-great-grandfather, Robert, and my great-great-great-grandfather, William. In my imagination, I’ll just keep piling on the pictures of great-grandfathers going further and further back in time. Remember, this is a thought experiment so not having actual photographs is not a problem. Now, stacking pictures of 185 million great-grandfathers – or great-grandmothers, had I preferred – is going to make for an awfully big pile. Even at three photographs per millimetre, the pile will soon get unwieldy. So, to make the stack more manageable, I’ll tip it on its side and pack the pictures along a single, winding bookshelf. It won’t be just any bookshelf, though. It will need to be 60 kilometres long! That’s approximately the distance between downtown Peterborough – let’s say the corner of George and Charlotte streets – to just east of Cobourg. Come along as I walk along the bookshelf and pull out pictures as I go. We actually know what most of my (and yours) distant ancestors looked like by studying fossils. Fossils can be dated, so we can say how long ago the fossilized animal lived. Keep in mind, however, that every picture in the line will look almost identical to the pictures before and after it. This is because change through evolution is very, very gradual. Think of yourself. There was never a day when you went to bed as a baby and woke up as a toddler. Our first stop is just 13 centimetres down the shelf at card 400. This represents about 10,000 years ago when my 400-greats-grandfather lived. Looking at his picture, we wouldn’t notice any real difference from a modern person – once he’d had a shower and a shave, of course. Carrying on, let’s stop at 1.3 metres down the sidewalk (one big step) and pull out a card from a hundred thousand years ago. Here we’d see a picture of my 4,000-greats-grandfather. Well, now, there would be a noticeable difference. His skull, for example, would appear a little bit thicker, especially under the eyebrows. Walking another 15 metres or so will take us to 1.25 million years ago and a picture of my 50,000-greats-grandfather. Now, we would be looking at someone dissimilar enough to count as a different species, the one scientists call Homo erectus. Homo erectus probably would not have been able to mate successfully (i.e., have viable off-spring) with a modern human, if the two were somehow to meet. It’s important to remind ourselves once again that all of this change was extremely gradual. We are Homo sapiens and our 50,000-greats-grandfather was Homo erectus. But, there was never a Homo erectus who gave birth to a Homo sapiens baby. Resuming our journey, we’ll stop next at six million years ago – just 80 metres down the bookshelf or half-way between Charlotte and King streets. This is where we’ll find a picture of my 250,000-greats-grandfather. He would be an ape and probably look a bit like a chimpanzee. However, he wouldn’t actually be a chimpanzee. He’d be the common ancestor that all humans share with modern chimpanzees. He would also be the 250,000-greats-grandfather of a chimp living today. One of his off-spring would have started the evolutionary branch that led to humans, while another would have begun the branch that led to modern chimpanzees. Carrying on, we’ll catch our breath in front of the Holiday Inn and pick out the card showing my 1.5 million-greats-grandfather. Yes, that would be a tail we’re looking at! This is not surprising, however, since even modern humans still have a tail bone. The coccyx is the final segment of the vertebral column and is the remnant of what was once a human tail. Over time humans lost the need for a tail, and evolution through natural selection got rid of it. Let’s see what the picture looks like if we stop at 63 million years ago, about 2.3 kilometres down the shelf at the corner of George and Lansdowne. Here we’ll see a photo of my seven million-greats-grandfather. He would look something like a lemur and be the ancestor of all modern lemurs, monkeys and apes, including us. Jumping in a car and driving south to Fraserville – passing an unbroken line of tightly packed photographs in the book shelf as we go – we’ll stop to look at the picture of my 45-million-greats-grandfather. He would also have been the ancestor of all modern mammals. Although family pride makes this hard to admit, this “Monkman” would have resembled a mouse-like shrew. By the way, he would also be a great-grandfather that you share with your cat, dog and hamster. At card 170 million – 56 kilometres from the beginning and approaching Cobourg – is where we’ll find my 170-million-greats-grandfather. This relative of mine would have lived about 300 million years ago. Family pride would have to be completely re-evaluated at this juncture, since he would resemble a big lizard. I could, however, take solace in the fact that he would have been the ancestor of all modern mammals, all modern reptiles, all modern birds and all of the dinosaurs. Another five kilometres east down the 401 will take us to the end of the shelf to just past Cobourg, where we’ll finally meet my 185-million-greats-grandfather. I would really have to brace myself because we’d be looking at a picture of a fish. Terrestrial animals did not yet exist. Now, we could, of course, go back in further in time but a lack of fossils makes it hard to know what these older great-grandparents would have looked like. We do know, however, that at about the 1100 kilometres mark – 3.5 billion years ago and somewhere close to the New Brunswick border – we would see a picture of the first life-form to exist on the planet. If our journey hasn’t impressed you enough yet, we could drive on to 4.5 billion years ago – somewhere around Moncton – and see a picture of our planet forming. Bouncing in the waves out over the mid-Atlantic – at 12 billion years ago – we could peer over the edge of the boat at pictures of the first stars dying in stellar explosions known as supernovae, in which helium and hydrogen atoms were transformed into never-seen-before atoms such as carbon, oxygen, phosphorous and iron – the stuff of life. At 13 billion years ago and approaching Ireland, we’d see hydrogen and helium atoms forming and gathering together to make the first stars. Finally, at 13.7 billion years ago as we dock our boat at Galway, Ireland, we would see pictures of the Universe flaring forth, expanding and cooling in what we call the Big Bang. Before that? Let’s just say that modern physics is working on it. Now, is reality not amazing stuff!

Side-bar: Great Backyard Bird Count The Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC) begins tomorrow, February 14 and continues through Monday. Simply count the birds you see over a 15 minute period – or longer if you wish – in one place, and report your results on line. Go to www.birdsource.org/gbbc/ for all the details. Be sure to explore last year’s Peterborough data by going to “Explore a Location”. |

|

|

Categories: Uncategorized