Peterborough Examiner – February 4, 2022 – by Drew Monkman

A look at how amphibians, reptiles, and fish endure winter

Whenever I’m out walking in the woods in winter, I often think of the many strategies used by animals and plants to survive this punishing season. Seen or unseen, awake or dormant, life carries on all around us. This week, I’ll take a look at how amphibians, reptiles, and fish get through winter.

Amphibians

As kids we were always told that frogs simply hibernate in the mud at the bottom of ponds. End of story. Although there are frogs who do opt for this strategy, just as many species actually tough it out on the forest floor. This group includes the spring peeper, chorus frog, gray treefrog and wood frog. With the onset of cold weather, they burrow down several centimetres into the damp leaf litter. Their metabolism slows to a crawl and, just like the leaves and moisture around them, they essentially freeze and become no less than “frogsicles”!

When the first ice crystals begin to form on the frog’s skin, adrenaline is released. It activates enzymes that convert glycogen in the liver to glucose. Blood and cellular glucose levels rocket to astronomic concentrations and, like the antifreeze in your car, the glucose lowers the freezing point of the cellular fluid. This protects the integrity of the cell.

At the same time, much of the water within the cells is withdrawn through osmosis. The water accumulates in the frog’s abdominal cavity and under the skin. Most of the water gradually freezes without harming any of the vital organs. Within only 15 hours, the frog is basically a block of ice. Even the eyes turn white because the lenses freeze!

During the many months of suspended animation, there is no breathing, blood circulation or heartbeat. All of the cells are therefore deprived of oxygen. By most definitions, the frog nearly qualifies as dead. However, when researchers bring these frogsicles inside and let them thaw out, the frogs quickly become active again.

Green frogs and bullfrogs have evolved along a different path. Both overwinter in the mud at the bottom of lakes and wetlands. They are able to absorb the little oxygen they need directly through their skin. Leopard frogs, however, usually prefer moving water which provides more oxygen. If you watch diving ducks on the Otonabee River in winter, you might see one come up with a hibernating leopard frog that they’ve plucked from the river bottom.

When it comes to the tadpoles of these same species, they remain active under the ice. A friend of mine, Ed Duncan has a large swamp near his house with a small, spring-fed area that never freezes. Every winter he finds a swarming mass of dozens of two-inch green frog tadpoles covering the whole expanse!

As for the American toad, it retreats to below the frost line, either by burrowing down into loose soil or by entering holes or crevices. This allows it to escape freezing temperatures altogether. Gardeners sometimes find toads when turning soil in the late fall.

Most salamanders in the Kawarthas also avoid freezing by seeking out shelter below the frost line. These locations can be as varied as animal burrows, tree root hollows, and rock crevices. Their metabolic rate drops dramatically, allowing them to survive for months with no food. Finally, aquatic salamanders like mudpuppies (very rare or absent in the Kawarthas) remain active under the ice all winter.

Snakes and turtles

Reptiles are not true hibernators. In other words, they don’t remain dormant the entire winter. However, because their heart rate and metabolism slow down, they can survive without food. This can mean six months without a meal!

Snakes also retreat below the frost-line into what are called hibernacula. These are underground chambers such as groundhog burrows, deep crevices in bedrock, or even manmade structures such as wells and building foundations. Hibernacula close to the water table are preferred because they keep the animals from dehydrating. Large numbers of snakes will often use the same site. On mild days, gartersnakes sometimes emerge from their hibernaculum and even bask on the snow. A large hibernaculum used by garter snakes is located in Mark S. Burnham Provincial Park.

Aquatic turtles survive winter by sinking down into the mud at the bottom of water bodies. By extending their head and legs to expose as much skin as possible, they are able to take up dissolved oxygen from the water. Some species can even absorb oxygen through blood vessels in the anal opening. Their heartbeat can slow to less than one per cent of the summer rate. This allows the animals to survive for extended periods of time, even when most of the oxygen in the water has been used up. However, they sometimes become active and can even be seen swimming under the ice.

In an interesting twist, when painted turtle eggs hatch in the fall, the hatchlings usually remain in the nest until spring. Unlike adults, first-year turtles are able to withstand freezing temperatures through the same mechanism as some frogs (see above).

Fish

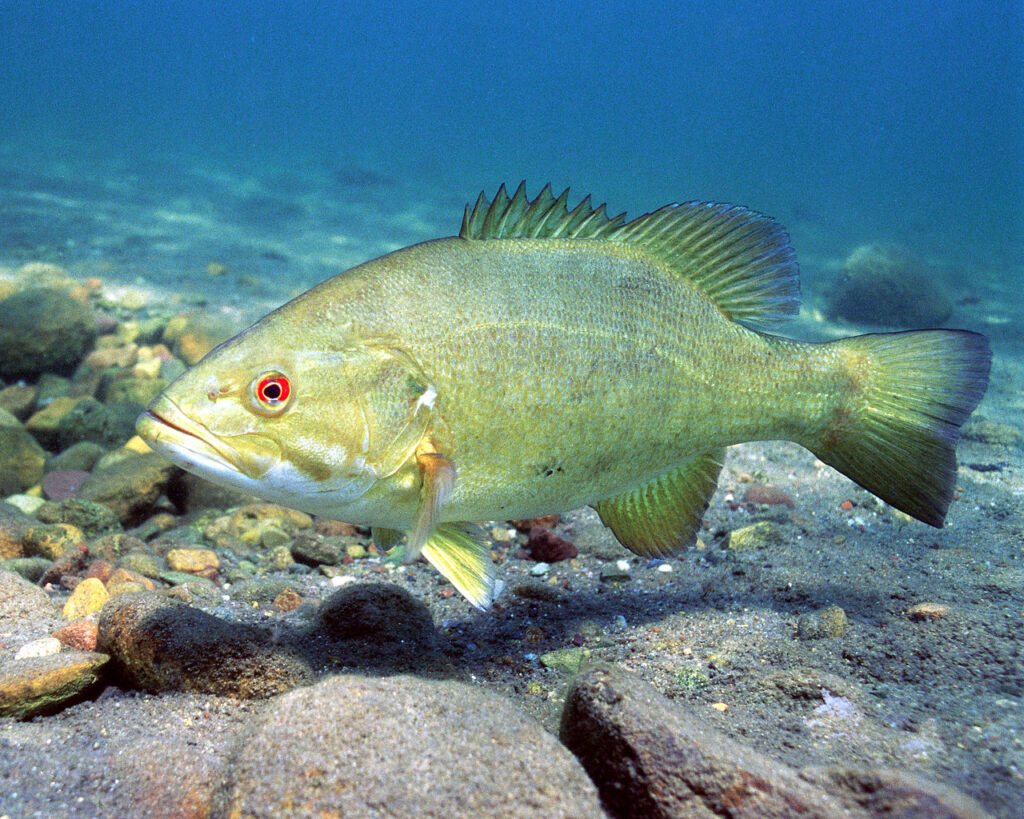

Although fish species such as bass are essentially dormant during the winter, other types of fish remain active and continue to feed. These include sunfish, walleye, yellow perch, northern pike, and all trout species.

As a general rule, fish stay close to the bottom until spring. Being cold-blooded, they congregate where the water is warmest, and activity requires the least energy. Most species also frequent the shallower sections of lakes where they patrol weed beds for food. Bass, however, lie dormant under logs or rocks until the light and warmth of spring restore their energy and appetite. This is why so few bass are ever caught by anglers at this time of year.

We should never think of winter as a boring season where nothing of interest is happening. The many ways animals ride out this challenging season are some of the true “miracles” of life on this planet. It’s something to think about the next time you explore our beautiful winter landscapes. I’ll conclude next week with an examination of the strategies used by invertebrates and plants.

CLIMATE CHAOS UPDATE

Alarm: The frightening rise of right-wing populism in much of the world is a clear and present danger for global action on climate change. Nor is Canada immune. What’s happened in Ottawa is just one example. Many populists completely reject the idea of human-caused global heating. They also repudiate decarbonization policies like carbon taxes and global initiatives such as the Paris Agreement. They see these measures as an elitist attack on the lives of ordinary people. The new brand of “freedom-loving” populists don’t even believe in expert opinion. Climate policy, like vaccines and pandemic restrictions, are seen through the lens of government curtailing our freedoms. For the future of this planet, we must push back against populism at every opportunity.

Carbon dioxide: The atmospheric CO2 reading for the week ending February 5 is 419.19 parts per million (ppm), compared to 416.89 ppm just one year ago. The highest level deemed safe for the planet is 350 ppm. The steady upward trend in atmospheric CO2 continues: Pre-industrial (280 ppm), 1912 (300), 1988 (350), 2010 (390), 2014 (400), and 2020 (413).

Take action: To see a list of ways YOU can take climate action, go to https://forourgrandchildren.ca/ and click on an ACTION button.