A group of dedicated young people is keeping a close eye on the health of local lakes

Not everyone would take delight in standing thigh-deep in muck to learn the difference between stinkpot and snapping turtles, but Rosalyn Shepherd was thrilled. The third-year environmental science student at Trent University is a volunteer in the Lake Guardian program, an initiative of the Environment Council for Clear, Stony and White Lakes. Rosalyn is one of 11 young people, aged 17 to 30, monitoring the state of the lakes this summer and building awareness around the many threats they face.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the Kawartha Lakes are under assault, be it from continued cottage and residential development, shoreline alteration, invasive species, winter water level drawdown, or warming water temperatures from climate change. Already this summer, we’ve had 19 days above 30 C. Two years ago, it was 28 days. How quickly we forget that in the 1990s, the number of days above 30 C averaged only 6.3.

With the quickly-increasing stress on aquatic ecosystems, it’s more important than ever to monitor these changes. Enter the Lake Guardians. In the process, these volunteers are increasing their own knowledge base and gaining invaluable field experience in monitoring techniques. The program is also helping the Environment Council build greater capacity in its mission to preserve and enhance the sustainability of the local watershed and enjoys the generous and enthusiastic support from cottager associations, along with the Stony Lake Heritage Foundation. Skilled local researchers, including professors from Trent University and Fleming College, have also been lending their expertise. The majority of the participants are students in environmental science programs at these schools. However, as a result of the current pandemic, there are far fewer opportunities for field experience. The Lake Guardian program is helping to fill this gap.

For Ed Paleczny, chair of the Environment Council, “It’s very inspiring to see the huge amount of enthusiasm and energy the volunteers bring. They are completely self-motivated and receive no pay. I’m also impressed by their knowledge of lake ecology and their expertise around the technology involved in doing monitoring work.”

A passion for nature

It comes as no surprise that all of the Lake Guardians have a personal interest in nature and aquatic ecosystems. Still, I’m always curious as to where this interest and passion comes from. Reading the volunteers’ bios on the Environment Council website, what stands out is their exposure to nature at a young age. Going up to Stony Lake was a big part of Rosalyn Shepherd’s childhood. She spent hours looking at and studying the lake’s plants and animals. Getting to know the lake is what made her realize she wanted to study environmental science. For Molly Ahmed, a grade 12 student, her love of the natural world comes from spending the last 13 summers at the family cottage on Clear Lake and taking part in environmental programs at Camp Kawartha and Juniper Island.

Jacob Rodenburg, executive director of Camp Kawartha, believes that a passion for nature and conservation is intricately linked to establishing a relationship with a specific natural area or parcel of land. This includes learning some of its species, seeing it change over the seasons, and feeling it become part of your “home”. This inspires a love for the area and the desire to protect it.

Guardian activities

Already this summer, the Lake Guardians have attended two training sessions. The first was a “turtle training” field workshop led by Josh Feltham, a professor at Fleming College. As Rosalyn described it in an article she wrote for the Environment Council website, “We learned about turtles from the seats of our canoes and thigh-deep in organic matter in a small bay of Stony Lake.” Among many other things, the Guardians learned how to protect turtle nests from predators and that snapping turtles don’t bite when in the water. “If you step on one while swimming, your toes are safe!” she explained. Monitoring the turtle populations will be an important part of the Guardians work this summer.

Reading about the turtle training reminded me of the huge increase in awareness and concern for these species. When I think back to the 1960s and the countless hours I’d spend catching turtles near my grandparents’ cottage on Clear Lake, I don’t recall any adults – other than my own parents – showing the slightest interest in turtles. Protecting them wasn’t something people even thought about.

The Guardians were also trained in aquatic plant identification at a session held in Gilchrist Bay. Much of the session focused on starry stonewort, a dangerously invasive, macro-alga that the volunteers are now monitoring and mapping using GPS technology. They will also be posting updates on its spread. Knowing where starry stonewort is present will be a reminder to boaters to either avoid these areas or at least check their motors for the plant remnants by which it spreads.

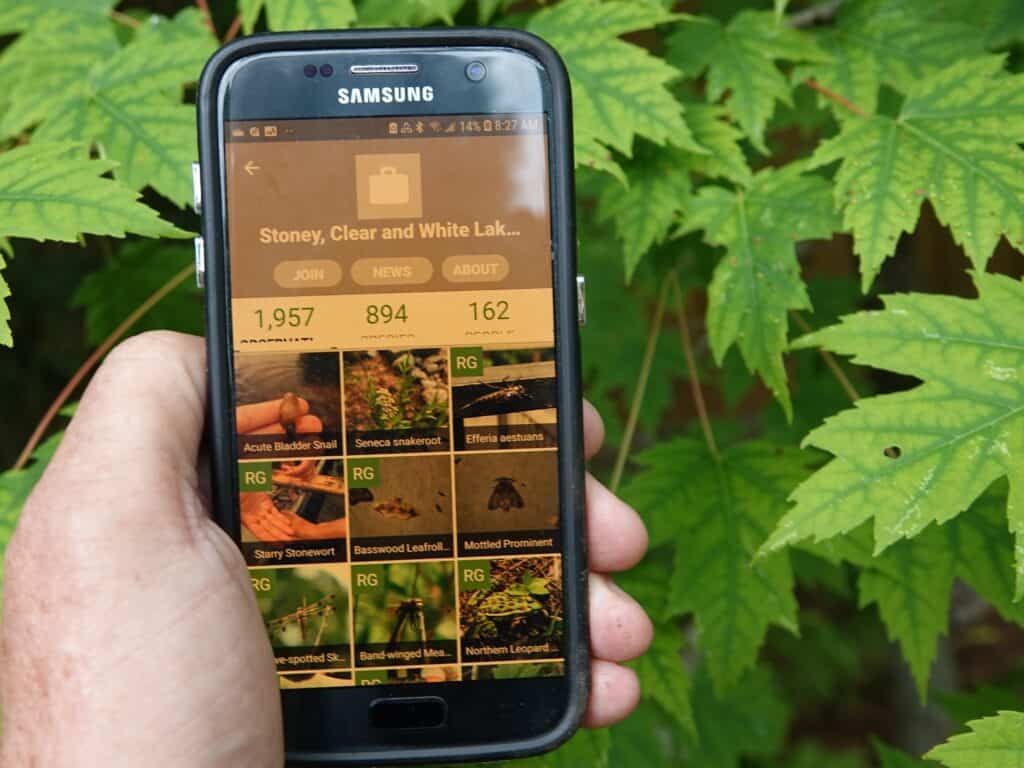

When it comes to species monitoring, the Guardians head out in canoes – always working in pairs – and explore the appropriate habitats. They then report their sightings using iNaturalist. This is an online citizen science project and social network of naturalists, citizen scientists, and biologists built on the concept of mapping and sharing observations based mostly on photos. I would encourage everyone to learn about this simple but powerful tool and to contribute your observations. Any observations you make on Stony, Clear, or White Lakes will automatically become part of the same data base that the Lake Guardians are building.

When not out on the lakes, the Guardians have also led Zoom-based outreach programs for youth and written articles on environmental topics of interest to the lake community.

Going forward

As for next year, the Environment Council hopes to set up 12 sites for long-term aquatic ecosystem monitoring. The information gathered from these sites will support future research to help the Council address some of the rapid changes they’re seeing in our ecosystems.

Looking at the larger picture of environmental protection, Ed and I both recall how our generation spent so much time amusing ourselves catching frogs and turtles, searching for salamanders under logs, or going fishing. Rarely were parents involved or even know what we were up to. The extent to which kids have these kinds of experiences today is unclear, but I do know that it’s more important than ever in forming future scientists and conservationists. The loss of biodiversity is happening so quickly. And it’s not just a decrease in plant and animal abundance. Increasingly, we’re looking at a complete loss of species. The study that came out this week on the bleak future of the polar bear is just another case in point. Closer to home, the majestic white pines that grace the islands and shoreline of Stony Lake may disappear completely in less than 50 years, given the rate at which the climate is changing. One can only hope that the kind of work being done by young people like the Lake Guardians will be a catalyst for unprecedented action on greenhouse gas reduction. Volunteer Kaleigh Mooney sees an interesting reason for optimism in this regard. “By involving the lake community in a citizen science project like Lake Guardians, it helps break barriers between academia and the public and builds trust between the two groups. In a world of climate change and resource degradation, this trust is so important.”

When it comes to addressing the onslaught of aggressions against the environment, it can feel like you’re holding a spoon against the flow of a river. But, as we soldier on, it’s heartening to see a new generation of conservationists like those keeping a close eye on local waters. As for Rosalyn Shepherd, she’s hopeful for the future of the lakes. ““I’m so excited that we have this program to help protect them and teach people how important they are.”

CLIMATE CRISIS NEWS

ALARM: As the RCMP investigation into the Columbia Icefield tragedy continues, the Edmonton Journal is reporting that a contributing factor may have been instability in the moraine – ground-up rocks, silt, sand, and ice strewn aside by the glacier as it moves – surrounding the terminus of the ice sheet. According to glacier expert, Dr. Jeffrey Kavanaugh of the University of Alberta, it’s possible that part of the steep slope of the moraine where the bus was travelling may have collapsed. “As the sediments (in the moraine) are warmed by the sun, it melts the ice,” said Kavanaugh. It can become runny and mucky and even cause a landslide. As global warming causes glaciers around the world to melt – the Athabasca glacier may entirely disappear by 2100 – unstable moraines are an emerging hazard in the mountains.

ENCOURAGEMENT: Britain’s Guardian newspaper has decided to put global CO2 levels on its weather forecast page. As CO2 levels continue to climb, the carbon count will serve as a daily reminder that we must drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions now. At an unprecedented 414 parts per million (ppm) as of July 20, the level of CO2 in the atmosphere is the highest it’s been in millions of years. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the level was 280 ppm. A concentration of 350 ppm is the highest seen as manageable. I would encourage people to ask Environment Canada, the Weather Network, the CBC, and CHEX-Global Peterborough to do the same on all their weather platforms, including on-air weather reports.

For local climate news and ways to take action, visit https://forourgrandchildren.ca/ and subscribe to the newsletter.