Wasps play a key role in pest control and pollination

Peterborough Examiner – August 30, 2024 – by Drew Monkman

As pleasant as a late summer outdoor meal might be, there always seems to be a handful of unwanted guests. More often than not, yellowjackets also show up. While it’s true they can be annoying and even deliver a painful sting, wasps like these deserve far more respect – and maybe even the kind of affection we reserve disproportionately for charismatic species like bees.

First, wasps are consummate predators. A colony of yellowjackets consumes about four kilograms of insect prey in a season. Most crucially, however, wasps are important pollinators. They are actually hairier than they appear and quite adept at transferring pollen from flower to flower.

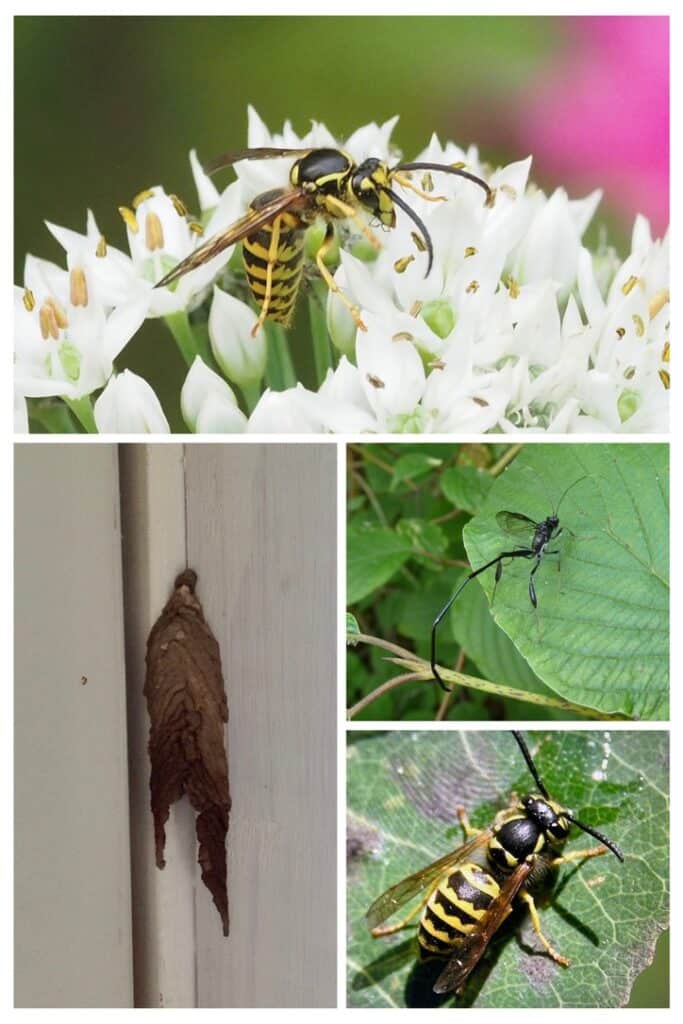

But, what exactly is a wasp? The word is a broad term that covers hundreds of thousands of different species and lifestyles. All have a well-defined and narrow waist, tapered abdomen, and appear smooth-skinned and shiny. The words “hornet” and “yellowjacket” are loosely used for wasps that build paper nests and have black and yellow (or white) markings.

People often refer to yellowjackets as “bees.” However, bees have a more robust build and are usually hairy. Their hind legs are flattened for collecting and transporting pollen. Unlike honeybees which have barbs on the stinger that cause it to break off when pulled out (thereby killing the bee), wasps lack these barbs and can therefore deliver multiple stings.

Yellowjackets

Yellowjackets are the most commonly-seen wasps at this time of year. One of the most abundant species is the eastern yellowjacket (Vespula maculifrons). It can be identified by the triangular, black, anchor-shaped marking on the segment of the abdomen nearest the thorax.

Like honeybees, yellowjackets live in colonies. To understand how these colonies function, we need to go back to last fall. Stocked up with a year’s supply of sperm after mating, young queens spend the winter hibernating alone in crevices. When spring arrives, each queen starts a new colony by gathering wood fiber to masticate into a pulp, which dries into a paper-like nesting material. Depending on the species, the nest is located in an underground cavity or aboveground attached to trees or buildings.

The queen starts the nest by constructing several hexagonal, egg-carton-like cells suspended from a short stalk and enveloped with a paper covering. She then proceeds to lay an egg in each cell. When the eggs hatch, the busy queen must feed the larvae small pieces of protein‑rich food such as bits of caterpillar or carrion. After about 12 days, the outer skin of the worm‑like larvae hardens into a tough casing. The developing wasp is now called a pupa and will undergo a radical change in form.

After another 12 days, an adult wasp emerges from each of the pupal cases. All of these individuals are sterile females called workers. They immediately set to work enlarging the nest and gathering food for the young. The queen, all the while, continues to lay eggs. As fall approaches, something unique happens. Sensing the shorter days, the queen begins to lay unfertilized eggs that will develop either into males (drones) or into new queens. These individuals will go on to mate. Only the newly‑fertilized females, however, have the ability to overwinter. The rest of the colony dies with the first hard frosts of fall.

A rush to find food

By late summer, especially when the season has been hot and dry, yellowjacket colonies can grow to thousands of individuals. Some will now have as many as 5,000 workers and a nest of 15,000 cells. The workers also tend to be most aggressive at this time, partly because the nest is a prime target for hungry raccoons and skunks.

The workers are also in a frantic rush to find protein to feed the many young still in the nest. However, by late summer insect numbers are decreasing. This forces them to also seek other sources of protein like that steak on your plate.

The workers also need to satisfy their own energy needs which is mostly in the form of sugars and carbohydrates from flower nectar – they love goldenrod! – ripe fruit, aphid honeydew and, surprisingly enough, from the larvae themselves. In an amazing exchange of material called trophallaxis, the larvae secrete a sugar relished by the workers. However, by late summer the larvae are producing less of this substance. So, when flowers don’t suffice, foraging workers often pursue other sources of sugar like those provided at restaurant patios and backyard barbecues.

To avoid getting stung, the rule of thumb is to leave the wasps alone and to refrain from swatting or swaying your arms. Another mitigation technique is to promptly clean up any food on the table and remove all trash. You might also try giving the wasps an offering like a slice of meat or a bowl of juice set out away from the table. They’re more than likely to simply go there.

Hornets

The bald‑faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata) is another common yellowjacket – despite its misleading name. It has a mostly black body with whitish markings on the side and face. Bald-faced hornets catch our attention because of their habit of building globular paper nests in trees. The nest starts out small but grows in progressive layers, often reaching the size of a basketball. As long as we don’t inadvertently disturb the nest, they pay no attention to us.

As for the true hornets, only one species, the non-native European hornet (Vespa crabro), is established in Ontario. Their body is mahogany in colour with dark red and brown coloring on the head and thorax. They tend to nest in wooded areas and rarely spread out elsewhere. The European hornet is frequently mistaken for the infamous northern giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). Also known as Japanese giant hornets or “murder hornets”, there are no confirmed sightings of this species anywhere in Canada outside of British Columbia.

Other wasps to know

You may also come across paper wasps like the northern paper wasp (Polistes fuscatus). This skinny red, black, and yellow wasp has dark wings and long legs. Paper wasps build their in unprotected paper combs with no paper envelope. It is suspended in a sheltered location such as under the eaves of buildings. These wasps rarely present problems since the colonies are usually small. Just let the nest be. Polistes have been found to be as effective as bumblebees at pollination.

The vast majority of wasp species are actually solitary, peaceful insects that don’t nest in colonies. One solitary wasp you may see around your house is the organ pipe mud dauber. They are shiny black except for the end part of the back leg which is whitish. They build pipe-shaped, mud nests that are attached to protected locations like a porch. Each nest contains two or three cells with an egg each. Mud daubers occupy the same site year after year.

Finally, about 70% of wasps are parasitic and don’t have stingers. They lay their eggs inside of insect larvae like woodboring beetles and caterpillars. In one huge group known as Ichneumonoidea, the females have extremely long ovipositors which are used to bore through wood and lay eggs in or on hosts deep inside. The larval wasp munches away on its insect host but the host doesn’t die until the wasp is ready to pupate. In recent years, parasitoid wasps have been released in Minnesota to reduce emerald ash borer populations and thereby protect ash trees. Researchers are optimistic that these tiny wasps may be turning the tide against the borers.

In her book “Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps”, Seirian Sumner delves into the question of what it would take to extend as much empathy to wasps as we do to bees since both are crucial to our ecosystems. She suggests that in a biodiversity crisis like the one we’re living through, “we have a responsibility to care about every aspect of nature, and not just the iconic, cute species that we find easy to love or appreciate.” This includes caring about wasps.