When I turned on CBC radio Monday morning, the first thing I heard was that the price of gasoline in London had dropped to less than 85 cents a litre. A quick check on ontariogasprices.com showed Costco in Peterborough selling gas at 86.9 cents. The near-universal reaction seems to be one of sheer delight, yet you might think that with all the attention climate change has received in recent months, more people would be expressing unease. In other words, why aren’t more of us connecting the dots and realizing that low gas prices mean more driving and, as we are now seeing, the increased popularity of larger, less fuel-efficient vehicles? The result, of course, is higher greenhouse gas emissions. The transportation sector accounts for about a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions in Canada.

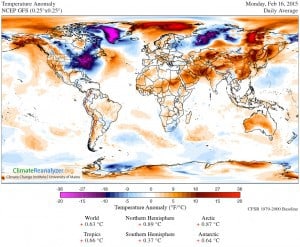

What’s wrong with the scenario? It’s not as if climate change hasn’t already touched our lives, at least for those paying attention. The outright balmy month of December 2015 was by far the warmest on record across the entire province. The mean temperature in Peterborough was an astounding 7.0 C above the 1981-2010 normal of -4.4 C and 7.9 C above the 1971 – 2000 normal of -5.3 C. This shatters the previous record, set in 2006, which was 4.6 C above normal. Yes, an exceptionally strong El Nino is being blamed, but most climatologists see climate change as setting the stage for El Nino’s intensity.

Whenever I write or Tweet on climate change in the Kawarthas, the amount of feedback I receive is limited. Other than the knee-jerk reaction from a couple of climate change deniers, the comments – or, in the case of Twitter, reTweets – are surprisingly few. As an active member of “For Our Grandchildren”, a local group that organizes events to educate and draw attention to the need for climate action, the attendance at many of our events has been disappointing, especially on the part of younger people. Two exceptions, however, were the excellent turnouts at an all-candidates meeting held during the federal election and a letter-writing event held just before the Paris climate conference.

Not a priority

What explains the lack of public engagement? A survey done last September by Dr. Erick Lachapelle, an assistant professor of political science at the Université de Montréal, is instructive. He has been doing similar surveys since 2011 and has found that climate change is not yet a priority issue for Canadians. Some of the key findings include: nearly half of us remain either uninformed or misinformed; a significant minority express uncertainty or doubt about the causes; more than half feel climate change will harm them only a little or not at all, and that it’s more of a problem for future generations; there is little understanding of policy tools like cap & trade; and, although most Canadians want more action on climate change, a majority remain unwilling to pay large sums to reduce emissions and increase the use of renewables. For example, only 14% would be willing to pay $250 or more per year to help the transition to a decarbonized economy. Lachapelle points out that even paying $250 per year is far below what the real cost would be. The take-away message seems to be “someone else should pay”.

Why the ambivalence?

In an interview on CBC Radio’s “Quirks and Quarks” (Dec. 12, 2015), Dr. Lachapelle was asked to explain these findings. He pointed out that climate change is a complicated, technical problem that requires a lot of motivation and time to be truly informed. Media coverage until recently has been sporadic (we rarely even hear about it on weather reports!), and for 10 years the Harper government never signalled to Canadians that climate change is an important issue. Lachapelle went on to say that humans tend to base their opinions on personal experience and are wired for short-term, immediate risks. Despite some glaring weather extremes like this past December, the winters of 2014 and 2015, and March 2012, most of us aren’t yet seeing huge changes in our day to day experience of the climate. It’s therefore easy to ignore risks in the future. Lachapelle added that once we accept the fact that humans are the primary cause of rising temperatures, the onus is on us to do something about the problem. Many people are unwilling to take this next step and to support paying the required costs.

To this list, I would add that humans are very susceptible to “shifting baseline syndrome”. When change happens gradually – as in the case of a changing climate – we hardly notice it. Because of our general disconnection from nature, many of us lack clear reference points as to how things used to be. This leads to an acceptance of degraded natural ecosystems and strange weather patterns as somehow “normal”. Very few of us are aware of the “canary in the coal mine” changes that are already occurring in the Kawarthas. We are already seeing changes in the dates of events (e.g., earlier flowering of plants, earlier return of some spring migrants); the arrival of warm-climate species from the south (e.g., opossum, giant swallowtail butterfly); more rapid growth and range expansion of plants that thrive on higher carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere (e.g., poison ivy, ragweed, dog-strangling vine); and a pattern of more extreme weather events.

What now?

How do we get past this ambivalence? More information about the causes will only take us so far. People filter information through their personal worldview and will interpret the same scientific findings differently in order to make it fit with how they think. For instance, accepting that climate change is a significant problem implies that government will have to play a greater role in solving the problem (i.e., take more of our money and establish more rules and regulations). People who are against greater government involvement in our lives are therefore likely to downplay scientific findings or even extreme weather. “I remember other green, mild Christmases. This isn’t anything abnormal,” is the kind of comment I heard a lot this holiday season.

Asked what can be done to make Canadians more attentive to this issue, Lachapelle highlighted the importance of framing climate change as something that is already affecting public health and security. He also talked about communicating and demonstrating the economic opportunities that will be created by transitioning away from a carbon-based economy. “I think this is an area where we need governments to lead and once it’s on the agenda… people will follow. We may be getting this leadership now, but only time will tell.”

When it comes to the health impacts of climate change, emotional distress is going to become a huge problem as we are forced to cope emotionally and financially with more extreme weather. There will also be a loss of sense of place as valued natural environments – the lake and landscape around the family cottage, for example – are degraded, much-loved species disappear and seasonal rituals like a backyard rink become a thing of the past. More about this in my next column. For now, let’s try to be a bit less jubilant about those low gas prices.