“In spring the moccasin flowers reach for the crackling lick of the sun…” Mary Oliver

For anyone with an interest in wildflowers, June is synonymous with orchids. At least a dozen species of this fascinating plant family bloom this month in the Kawarthas, and the spectacle is not to be missed. In addition to their exquisite colours and designs, orchids are a wonderful testament to the power and wonder of evolution.

Peterborough County is home to 36 orchid species of which 14 are considered rare or their presence is based on old records. Species belonging to the genus Cypripedium, commonly known as lady’s‑slippers, are the most renowned. The Kawarthas boast four species. Probably the best-known member of this genus is the pink lady’s‑slipper, also known as the moccasin flower. It is usually found in dry, upland sites, quite often in association with pines. The Nanabush Trail at Petroglyphs Provincial Park is often a good place to find them.

The largest of our native orchids is the showy lady’s‑slipper, which measures up to 80 cm in height and occurs in open to semi‑shaded wetland edges. This species requires 10 years of growth from germination to the time it flowers. They can be found throughout the region, including wetlands along Clifford Road, just east of County Road 38 near Warsaw.

Dry to moist calcium‑rich sites are the preferred habitat of the yellow lady’s‑slipper. This species, too, is widespread in the Warsaw area and often grows along roadsides. The edge of the wooded swamp along the road leading from the main gate to the campground in Warsaw Caves Conservation Area has been a good spot in the past.

The Kawarthas is also home to the lesser-known ram’s‑head lady’s‑slipper. They prefer cold, undisturbed wetland edges and are often found in association with white cedars. I have found these at the south end of the Miller Creek Conservation Area.

A rich local history

The Kawarthas has long enjoyed a special status among orchid lovers. “Our Wild Orchids”, the first book on Ontario’s orchids, was researched and written in the 1920s by Frank Morris. I believe there is still a copy at the Peterborough Public Library and in the Trent University Library Archives. Some of the most interesting passages are his vivid descriptions of orchid‑searching trips to the Cavan Swamp, Warsaw area, and Stoney Lake. In one passage he writes: “Elma and I drove up through Warsaw and Gilchrist’s Bay … and there in the heart of ‘Cypripedium Bog’, in a thicket of old cedars close to a limestone ridge, I found 23 flowering plants of Calypso…the hidden fairy nymph.” This species is considered the most exquisite of Ontario’s orchids. I am not aware of any local sightings, however, since the late 1970s.

Reading Morris’s book is a reminder of how much more abundant orchids used to be. Because of habitat loss, indiscriminate picking, and digging up for transplanting into gardens, most orchid species have declined greatly in number. I recall that the late Doug Sadler – a renowned Ontario naturalist and my predecessor as nature columnist for this paper – once told me that in the 1950s people used to sell bouquets of showy lady’s‑slippers at the Peterborough Farmers’ Market!

A wonder of evolution

One reason I’m intrigued by orchids is that they have so much to tell us about evolution. They show amazing adaptations – or contrivances, as Charles Darwin described them – to attracting and exploiting their insect pollinators. In his book “Fertilization of Orchids”, Darwin explained in detail the complex relationships between these flowers and their pollinators and how this led to the co-evolution of both. Darwin’s work provided the first detailed demonstration of the power of natural selection.

Co-evolution between orchids and insects has led to an incredible amount of diversity. In fact, with close to 30,000 different species, orchids represent the world’s largest plant family. They are also an incredibly old family. The first orchids are believed to have appeared some 80 million years ago and would have co-existed with dinosaurs. Despite the huge number of species, most orchids tend to be uncommon and almost never dominate a given landscape. Paradoxically, they produce seeds in astronomical quantity ‑ well over a million in some species.

The pink lady’s-slipper provides a great example of the complicated dance between orchid and pollinator. Its sweet odour and enticing pink pouch – a modified petal – attract bumblebees. On the hunt for nectar and pollen, these large, hairy insects pry their way into the large, slipper-like pouch through the incurved slit down the front. Once inside, the slit closes and traps the hapless bee. Exiting by where it entered therefore becomes impossible. But, it’s not all bad news for the bee. The upper part of the pouch is lined with sticky hairs coated in nectar, and there are translucent areas where light shines through. Attracted by the light and sugar reward, the bee climbs upwards to gather nectar and to make its escape. The pouch is constricted, however, below two small exits to the outside. In order to regain its freedom, the bee must crawl under a large flattened structure. As it does so, the insect’s back rubs up against the stigma, the female part of the flower. Any pollen sticking to its body – presumably from another orchid it visited earlier – is scraped off. Bingo! The orchid is pollinated. But one last bit of trickery still remains. As the bee finally makes its way out of one of the strategically-located exit holes, it inadvertently rubs up against a sticky mass of pollen grains, which adheres to its back and sides. If it enters another lady’s-slipper, the bee will follow the same path and unwittingly leave behind pollen once again.

Despite this elaborate pollination mechanism, pink lady’s‑slippers seem to spread mostly through their rhizomes. Rhizomes are underground, creeping stems that are capable of forming new plants. This explains why, unlike most other native orchids, lady’s-slippers of all species are sometimes found in large masses.

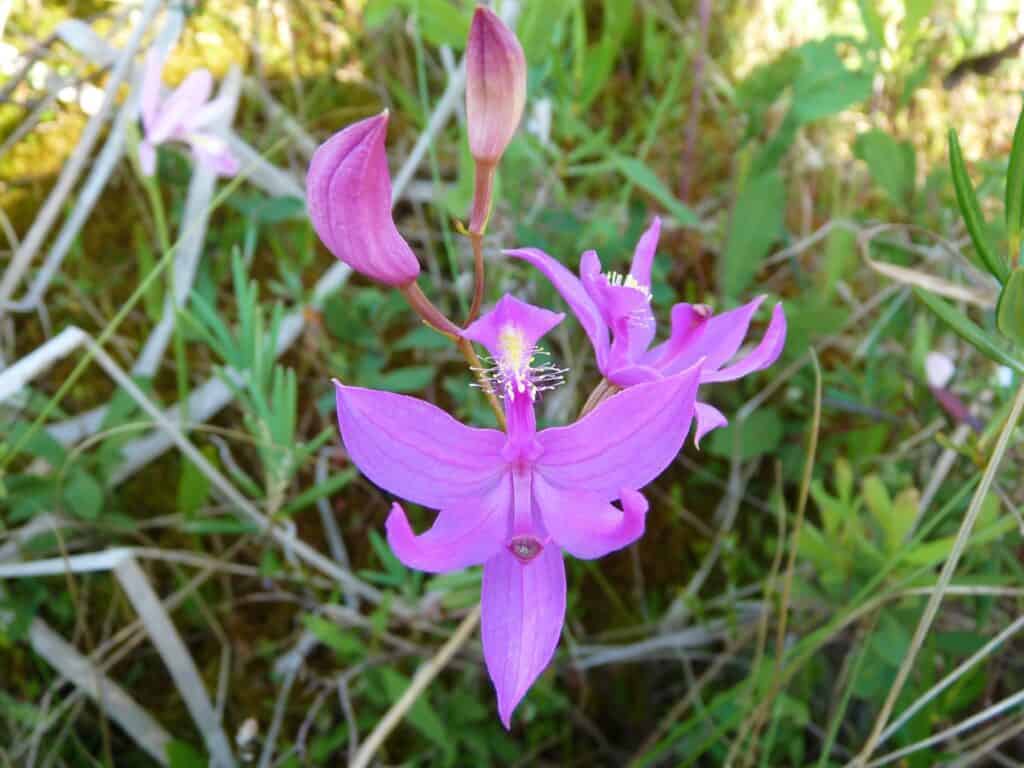

In late June and July, three other species take centre stage. Their flowers, too, have a unique design. They are the Arethusa (dragon’s‑mouth), Calopogon (grass‑pink) and rose pogonia (snake‑mouth). All three are pink in colour and grow in the acid soil of bogs and wet meadows. All can be found in Silent Lake Provincial Park. I recommend paddling into “Third Silent Lake” at the south end of the park where the sphagnum bog is home to large numbers of grass-pinks, rose pogonias, and other typical bog species like pitcher plant and sundew.

Arethusa photo from Wikimedia. Others by Drew Monkman

Pollination for these species, too, depends on some very clever adaptations. In the case of Calopogon, bees are immediately attracted to the top petal of the flower because of a mass of stamen‑like objects, which appear to be loaded with pollen. However, upon landing on these hairs, the insect quickly realizes there is no pollen to be found. But, before it can fly away, the bee’s weight causes the petal to collapse downward. The woeful bee ends up on its back, pinned against a trough‑like appendage that contains the true sexual parts of the flower. The bee’s hairy back may pick up sticky pollen located here or transfer pollen ‑ from a previous visit to another Calopogon ‑ to the stigma, thereby assuring pollination. Evolution rarely takes the easy route to solving the challenges of reproduction!

Blooming timetable

Orchids, like all plants, follow a definite blooming schedule. Most of the lady’s‑slippers bloom in late May through mid‑June. Showy lady’s‑slipper, however, along with Arethusa, Calopogon and rose pogonia, usually bloom in late June. The latter can sometimes still be found in flower as late as mid‑July. Later in the summer, watch for spotted coral‑root (July), dwarf rattlesnake‑plantain (late July and August), and nodding ladies’‑tresses (late August and September). Once again, Silent Lake (Bonnie’s Pond Trail) and Petroglyphs Provincial Park (Nanabush Trail) is a good place to try for all three of these summer‑blooming species. Ladies’-tresses also grow in damp areas along the edge of the Trans-Canada Trail, just east of Highway 7.

(Drew Monkman)

It’s important to resist the temptation to dig orchids up and transplant them into your garden. Not only does this put the species further at risk, but it is rarely successful. Orchids depend on a special relationship with fungi. Without the presence of the right fungi in the soil, most orchids will not survive. Take all the pictures you want, but please let them be. An excellent online resource for orchids can be found at ontariowildflowers.com.

CLIMATE CRISIS NEWS

As COVID-19 and the unparalleled public outcry against racism occupy nearly all of the media’s attention, we might need reminding that the climate crisis is only getting worse. Last month was Earth’s hottest May on record. At the same time, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere hit a record 417 parts per million (ppm), up from 414.8 ppm the previous May. Before the Industrial Revolution, global average CO2 was about 280 ppm. What’s more, the 12-month period that ended in May saw average global temperatures reach 1.3 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial norm. The consensus among climate scientists is that we must avoid warming of more than 1.5 degrees above that benchmark.

The racial inequality crisis is also intertwined with the climate crisis. People of colour disproportionately bear climate impacts, from storms to heat waves to pollution. We also need people of all races involved in this fight. Diversity of opinion and perspective leads to better decision-making and more effective strategies. We need to work on both at the same time, just like we need to recognize that the emergence of new deadly viruses will only increase as climate change worsens.