Peterborough Examiner – February 4, 2022 – by Drew Monkman

Evolution has conferred birds and mammals with intriguing adaptations.

One of my most frequent bird sightings this winter might surprise you. It’s the American robin. People often ask me, “How in the world are robins able to withstand the cold?” As it turns out, bird and mammal survival in winter is a multifaceted topic and one I’ll explore this week.

The average temperature in January this year was a bone-chilling -12.5 C. This is a full 3.6 C colder than the 1971-2000 average. But, as our planet heats up, warmer-than-average months in the Kawarthas are twice as likely as cooler-than-average. So, what might be happening this year?

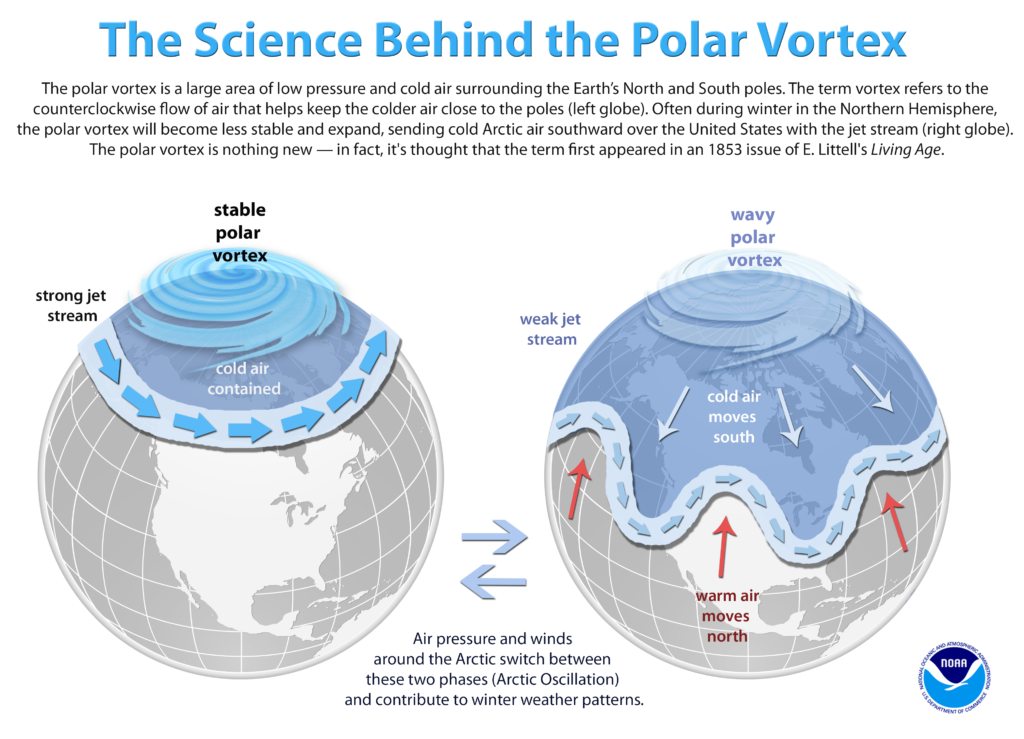

Normally, frigid Arctic air is held back by air currents known as the jet stream. However, an increasing number of scientists think that climate change is causing the jet stream to weaken and bend like an “S” on its side. This appears to be allowing frigid Arctic air to spill much further southward and remain for days.

Bird survival

Feathers are a bird’s first line of defense in winter. They provide extremely efficient insulation from the much colder surrounding air. Using small muscles to fluff up their feathers, tiny air spaces are created that drastically reduce heat loss. This is the same principle that explains why down jackets are so warm.

Birds can further reduce heat loss by burying exposed body parts into their feathers. For example, they will often tuck their bill into their shoulder. But what about their exposed legs? The answer lies in an amazing network of blood vessels that minimizes heat loss. Warm arterial blood moving towards the bird’s feet passes through a network of small passages in close proximity to the cold venous blood returning to the heart. Heat is exchanged from the arterial vessels to the venous vessels keeping heat loss minimal.

Shivering, too, helps birds avoid hypothermia. Perched birds must continuously shiver to keep warm in cold conditions. This happens even during sleep. Shivering produces heat at five times the bird’s basal rate. However, when you consider that a bird needs to maintain its core body temperature at about 42C, and that the surrounding air may be more than 70C colder, a great deal of fat must be burned to fuel the shivering process.

It’s therefore essential that birds get enough to eat during the day to maintain fat reserves. A chickadee, for example, only has enough fuel to get through a single night. It needs to feed every day to survive. As for robins, there’s an abundance of wild food this winter (especially wild grapes) to keep those fuel reserves topped up.

Some birds can also lower their internal body temperature. This reduces the difference with the air temperature, thereby further reducing heat loss. Less shivering is necessary and fat reserves are used up at a lower rate. A chickadee can lower its core temperature from 42 C to 30 C during a long winter night. It actually becomes temporarily unconscious.

As a final line of defense, birds take shelter at night, usually in dense vegetation such as conifers. Chickadees, nuthatches, and bluebirds will also use tree cavities and even nesting boxes. On several occasions, I’ve even seen a chickadee whose tail is still crimped from a night spent squeezed in some tight hollow.

Mammals

Evolution has also provided mammals with many ways to deal with the cold and lack of food. The most familiar is hibernation, which is a special kind of dormancy. Dormancy or “torpor,” is an adaptation by which an animal slows down its metabolism and avoids having to eat at a time when food is scarce or absent. It’s essentially an energy-saving phenomenon. To survive dormancy, animals live off stored body fat. However, not all dormant animals hibernate. To qualify for hibernation, there must be reduced breathing and heart rate, along with a lower body temperature.

Only a few mammals in the Kawarthas are true hibernators. These include groundhogs, bats, and the beautiful woodland jumping mouse. During its five-month hibernation, a groundhog’s heart rate falls from 90 beats per minute to only 5; its body temperature plummets from 37 C to 3 C; and its breathing rate drops from about 16 breaths per minute to as low as 2.

Many mammals are dormant for extended periods during winter but aren’t true hibernators. They maintain near normal body temperature and awaken frequently. Chipmunks, for example, spend the winter in their network of underground chambers. They sleep for a few days, awaken to have a snack in a chamber where they’ve stored food, take a bathroom break in another room, and then return to their sleeping quarters.

Raccoons and skunks rely mostly on body fat for survival. However, when temperatures drop below freezing, they sleep for long periods in locations such as abandoned burrows, hollow logs, culverts, buildings, or even under a deck. Both of these species may become active again during mild spells.

Bears aren’t true hibernators either. Although their heart rate slows down from about 50 beats per minute to 10, a sleeping bear’s body temperature only decreases by about 5 C. What’s most amazing, however, is that bears don’t have to drink or urinate while in dormancy. They essentially shut off their kidneys and are able to biochemically recycle urea from their urine back into protein. In this way, there is no loss of muscle tissue. Nor do bears suffer from osteoporosis (loss of bone mass), even after months of inactivity.

As for mice, voles, and shrews, most remain active by taking advantage of the insulation provided by snow cover. The air temperature under a blanket of snow rarely falls below freezing. They search for food in a network of tunnels under the snow. You can easily see these when the snow melts.

Deer, foxes, weasels, beavers, and squirrels are also active in winter. As for squirrels, when cached nuts or birdfeeder offerings don’t suffice, watch for them feeding on keys, high up in maples. You may even see them entering or exiting their well-insulated tree nests (dreys) which provide critical shelter from the cold.

Maybe the best way to enjoy mammals in winter is to get to know their tracks. To get started, go to the Ontario Parks blog at https://tinyurl.com/2p8szem4

Next week, I’ll look at how reptiles, amphibians, and fish deal with the challenges of winter.

CLIMATE CHAOS UPDATE

ALARM: Doug Ford and the PCs haven’t just stalled on climate action; they’ve been actively hostile. As just one example, Ford cancelled Ontario’s cap-and-trade program which led to the scrapping of numerous green initiatives like rebates for electric vehicles. Now, internal government forecasts reveal that the Ford government is nowhere near to achieving Ontario’s greenhouse gas emission-reduction targets. Present “committed policies” will achieve less than 20 per cent of the targeted cuts, and future policies like building Highway 413 will actually increase emissions by putting more cars on the road. See https://tinyurl.com/2p9a6xyw

CO2: The atmospheric CO2 reading for the week ending February 4 was 417.19 parts per million (ppm), compared to 415.15 ppm just one year ago. The highest level deemed safe for the planet is 350 ppm. The steady upward trend in atmospheric CO2 continues: Pre-industrial (280 ppm), 1912 (300), 1988 (350), 2010 (390), 2014 (400), and 2020 (413). Rising CO2 means worsening global heating and climate chaos ahead.

TAKE ACTION: To see a list of ways YOU can take climate action, go to https://forourgrandchildren.ca/ and click on an ACTION button.