Most readers are probably now aware that the Royal Canadian Geographical Society has chosen the gray jay as Canada’s national bird. It beat out better-known contenders like the common loon and snowy owl in a countrywide vote, followed by a panel debate. Personally, I think the gray jay fits the bill from every perspective. If you have ever “met” one, you will understand how easy it is to fall in love with these tame, gentle birds. And, if you were looking for a bird that represents our great northern forests and the tenacity of life in the dead of winter, this is the species.

Only slightly smaller than its blue-feathered cousin, the gray jay is a study in black, white and grey. It has a soft, almost rounded appearance, thanks to its short bill, large eyes and fluffy plumage. The gray jay’s silent, gliding flight and soft melodious call notes project this same aura of softness. You can almost think of it as an inflated chickadee – and equally friendly! Some would also argue that the gray jay’s lack of flamboyance is a good match with the nature of Canadians.

Behaviour

Gray jays – or Canada jays as they were once called – are both tame and venturesome, two characteristics that endear them to people. They seem to have an instinctive sense that humans are an easy source of food. They are well known for visiting hunt camps, traplines, nordic ski trails and backcountry campsites. They will take just about any edible scrap. Gray jays often shared meals with the men and women who built our nation – explorers, prospectors, lumberjacks, north country settlers – and no doubt eased their loneliness. They are also known as “camp-robbers” and “whiskey jacks”. The latter name was derived from “wiskedjak”, an Ojibwa word meaning a mischievous spirit who liked to play tricks on people. Choosing the gray jay as Canada’s national bird honours our First Nations. Gray jays are permanent residents. They do not migrate – not even for short distances. Mated pairs occupy a territory of about 70 hectares, which they sometimes share with a third, non-breeding individual. Staying put may partly explain why they are so long-lived – up to 16 years.

Gray jays have evolved to store food as an adaptation to surviving the winter months. Food items are saturated with sticky saliva from the bird’s enlarged salivary glands. The saliva coagulates on contact with air and becomes a viscous glue, which is used to cement the food to nooks and crannies in trees. They guard against thievery from other species by covering their food caches with a piece of bark or lichen. Gray jays can make hundreds of caches in a single day, especially in late summer and early fall when food is plentiful. This will provide nearly all of the nutrition they need from November through May. What is most astonishing, however, is that the birds actually remember where they have hidden their food! Maybe this isn’t so surprising, since gray jays belong to the Corvid (crow) family, arguably the smartest birds on the planet. The jay’s habit of putting away resources for future needs is an important lesson to all Canadians, especially at this time of record personal debt.

Nesting

Gray jays begin nesting in early March, when sub-zero temperatures and heavy snow cover rein supreme. One reason the young are able to survive the cold is superb nest construction. Unlike the blue jays’ flimsy nests, those of the gray jay are bulky, deep and well insulated. They are lined with feathers and even bits of fur. The three or four nestlings are fed food that the parents cached the previous year. By nesting early, the young get a head start on amassing the food stores they will need to get through their first winter.

Juvenile gray jays are a sooty grey all over and almost look like they belong to a different species. In June, they begin a serious struggle for dominance. The young jays chase each other more and more aggressively until one of them will have expelled its siblings from the parents’ territory. This more dominant bird will continue to live with its parents for two or three years, or until a nearby territory becomes available. This is why you often see gray jays in groups of three. Sometimes, however, the third bird is an “ejectee” from another territory that is now living with unrelated adults. The weaker siblings are forced to leave the territory and most will die before winter arrives. This strange behaviour on the part of young jays makes evolutionary sense. They are probably not skilled enough to store sufficient food for their first-winter needs and have to rely on help from adult birds. It is unlikely, however, that there would be sufficient food for a second or third juvenile, hence the fight for dominance.

Range

Gray jays are found from coast to coast in Canada and in all of our provinces and territories. In Ontario, their range extends from the edge of the tree line in the north to the last isolated spruce bogs where the Canadian Shield meets the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence Lowlands in the “Land Between”.

However, you won’t find gray jays in our towns and cities. This might make you wonder why we would want a national bird that so few of us can easily observe first-hand? David Bird, Emeritus Professor of Ornithology at McGill University, argues that this very fact might motivate more Canadians to visit the northern forests to see their national bird and learn more about its increasingly threatened habitat.

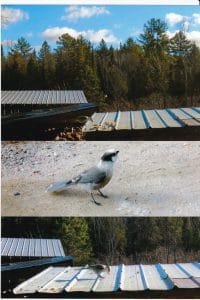

Gray jays can still be found in the northern Kawarthas, although their numbers are decreasing. Up until about 15 years ago, at least one pair had a territory at the Kawartha Nordic Ski Club north of Woodview. Skiers would enjoy sharing a few bread crusts or sunflower seeds with the birds at the Tanney Cabin. They were also present in Petroglyphs Provincial Park and in the Apsley area. In “Our Heritage of Birds” (1983), Doug Sadler wrote, “In winter, gray jays…have been found even in the southern parts (of Peterborough County) as early as September and as late as April (Miller Creek Conservation Area). They sometimes visit feeders.” The birds Sadler describes were probably immature jays, which had been forced out of their parents’ breeding territory.

There is still a pair of gray jays coming to a feeder on County Road 507, north of Flynn’s Corners. There are also occasional sightings from the large bog on Jack’s Lake Road south of Apsley and even scattered reports from Petroglyphs Provincial Park. Whether there is still a breeding pair at these locations is unclear, however. Just this week, I also learned of a lone gray jay spotted on Algonquin Boulevard in Peterborough.

Your best chance of seeing and feeding gray jays, however, usually requires a trip to Algonquin Park. Late fall and winter is an excellent time to find them on Opeongo Road, at the top end of the Mizzy Lake Trail and on the Spruce Bog Trail between the parking lot and the boardwalk. If you hold out food, they will glide down from a tree and land on your bare hand. The sensation of the bird’s talons on your skin and the close-up view of their fluffy plumage and big black eyes are unforgettable.

You will also be able to witness their caching behaviour. When you share food with jays, they hardly eat any of it. Instead, they continually fly back into the forest and conceal each tidbit. Your handouts are being transformed into survival insurance. How can you not be impressed!

Climate change

Even in Algonquin Park, gray jay populations have suffered a marked decline in recent decades. The population is only half of what it was in the 1970s. It may be that a warming climate is speeding up the decomposition rate of perishable food caches like insects and pieces of meat. In other words, the birds’ natural refrigerator is failing. This, in turn, may be making winter survival and successful nesting more difficult.

This hypothesis comes from a decades-long study of gray jays in Algonquin Park by Dan Strickland, a former head naturalist. Annual air temperature in the park has been increasing by about 0.7 degrees Fahrenheit per decade. Habitat that once supported breeding jays, including many areas along Highway 60, is now abandoned. The worst losses have been in areas dominated by hardwood forests, while the least attrition has occurred in boggy, lowland areas covered with spruce. It is thought that the antibacterial properties of spruce bark and resin may help preserve cached food.

Despite – or maybe because of – the many challenges the gray jay faces, I am delighted with its choice as our national bird. Although the loon, snowy owl and chickadee would have also fit the bill, the gray jay is something fresh and new and just might encourage people to get outside and to explore the north – if only Algonquin Park. For that reason alone, you have to like the selection. And, just in case you are a stickler for Canadian spelling, please note that the bird’s official name is indeed gray jay and not “grey jay”!