“Lichens are fungi that have discovered agriculture” – lichenologist Trevor Goward.

Of all the conspicuous organisms in the landscape, lichens are probably the most overlooked. They are not rare, but people who see and appreciate them are few and far between. The eye cannot see what the mind does not already know. When you begin to pay attention, however, you will see lichens everywhere, starting with those curious, crusty green patches on the bark of mature maple trees on your street. In fact, the Kawarthas is home to hundreds of lichen species. With far fewer plants to compete for the eye’s attention, winter is a great time to get to know these hard-to-classify organisms.

Lichens are found in places where almost no other organism can survive. The type of substrate (surface) they grow on is often the first step in identifying them. Some species flourish on the ground, which can include bare soil, sand, humus, rotting logs and stumps. Others make a living on sun‑scorched rocks or cliff sides. Still other species prefer the bare bark and branches of deciduous and coniferous trees. Old trees often have the most lichen diversity – the bark of a single sugar maple may harbour a dozen species or more. The substrate’s only purpose, however, is to provide a surface to which the lichen can attach.

Biology

Lichens are actually dual or even triple organisms, consisting of a fungus, an alga and/or a cyanobacterium (blue-green algae) living together as a single unit. The latter two organisms – the “photobionts” – use sunlight to photosynthesize glucose both for themselves and for the fungus. Fungi are incapable of making their own food. In turn, the fungus provides a home and protective cover for the photobionts, protecting them from damaging ultraviolet rays. This type of mutually beneficial relationship in nature is called symbiosis.

Although lichens are presently classified as part of the fungi kingdom, this is only a classification of convenience. Algae belong to the protista kingdom, while cyanobacteria are in the monera kingdom. In this respect, lichens are as much tiny ecosystems as they are individual organisms.

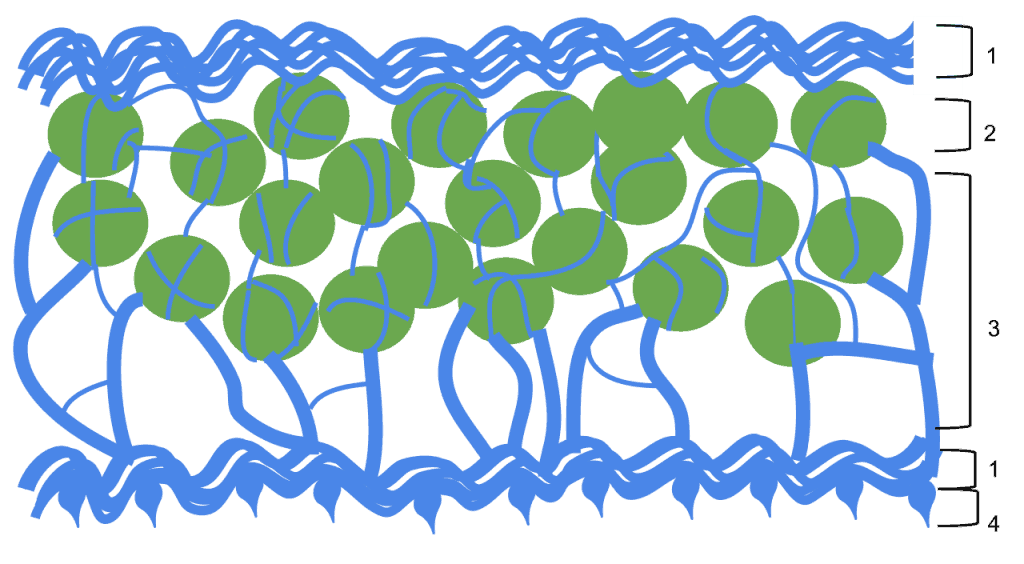

If you look at a cross‑section of a lichen body (thallus) through a 10x hand lens, you will find a protective outer skin (cortex) of fungal cells. This covers the photobiont layer of single-celled algal and/or cyanobacteria cells, which are mixed in among branching fungal filaments (hyphae). Finally, there is a third layer made up strictly of hyphae. Although lichens have no roots, they do have fungal strands called rhizines that attach the under surface of the lichen to the substrate.

Cross section of a typical lichen 1. Cortex (thick layers of hyphae) 2. Photobiont (algae or cyanobacteria) 3. Loosely packed hyphae 4. Rhizines (anchoring hyphae) – J. Durant via Wikimedia

Lichens are classified by the type of fungi they contain – usually a species in the ascomycete group. These fungi lack the typical mushroom cap and stalk and will only grow in a “lichenized” state. In other words, they can only survive when living in tandem with algae and/or cyanobacteria. They represent about a quarter of all fungal species. Conversely, the algae and cyanobacteria in lichens can live on their own. Many experts now refer to lichens as lichenized fungi or, more poetically, “fungi that have discovered agriculture.”

Growth forms

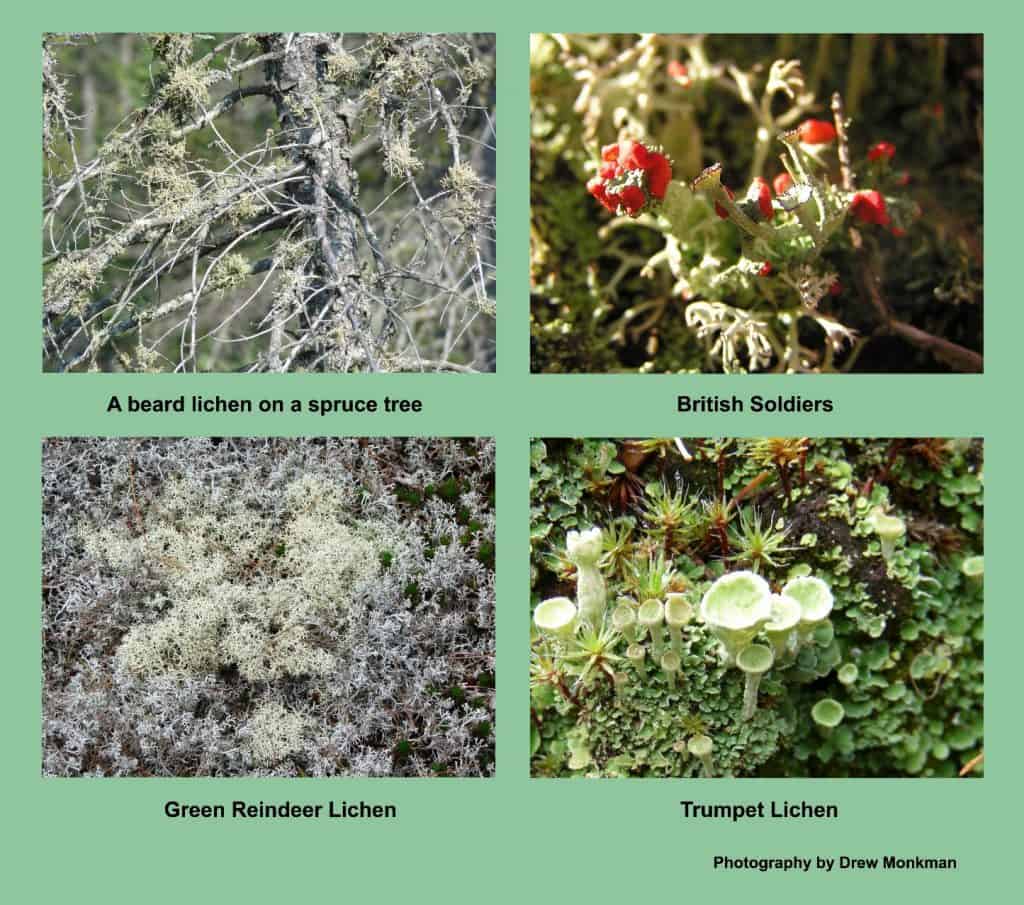

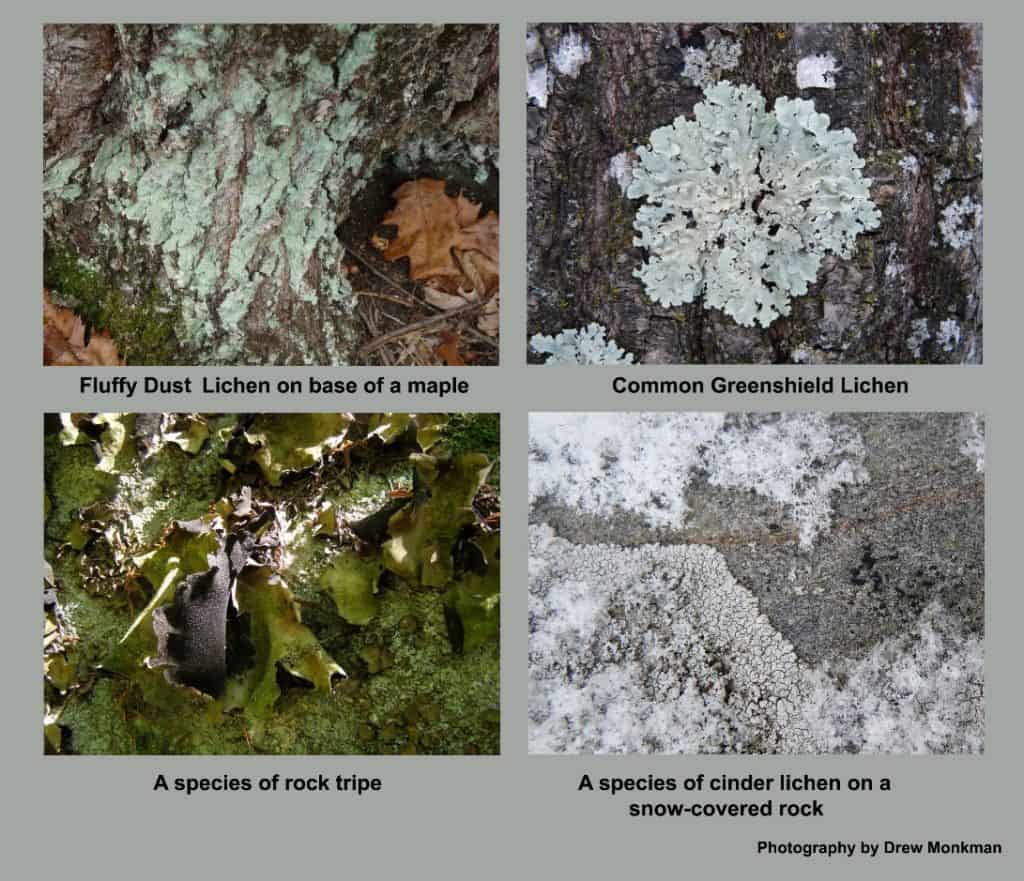

Lichens have been divided into three subgroups, based on differences in growth form. Foliose lichens (e.g., Rock Tripe) look somewhat like leaves and often have cup-like fruiting bodies (apothecia) that produce spores. Fruticose lichens (e.g., Reindeer Lichen) resemble shrubby or bushy growths, which stand upright or hang from branches. Crustose lichens (e.g., Dust Lichen) often bring to mind paint or powder sprayed on a tree or rock.

When and where

Lichens can be seen year-round, even now in the depth of winter. They survive the cold by drying out to the point of becoming brittle. If temperatures climb above freezing, however, and if sufficient moisture becomes available, photosynthesis can take place and the lichen will even grow.

Because the Kawarthas overlaps two physiographic regions – the Canadian Shield to the north and the St. Lawrence Lowlands to the south – we enjoy especially rich lichen diversity. Each region offers different substrates, especially in terms of geology and tree species. For example, some lichens prefer to grow on limestone (southern Kawarthas), while others opt for granite (northern Kawarthas). Some especially good lichen habitats include granite ridges and conifer swamps (e.g., Petroglyphs Provincial Park), limestone ridges (e.g., Warsaw Conservation Area) and hardwood stands with large sugar maples (e.g., Mark S. Burnham Provincial Park). Even Peterborough itself offers great lichen viewing. Look for them on old brick walls, gravestones, roofs and the trunks of mature trees.

A few lichens to get to know

A word of warning. It is not always easy to identify lichens to the species level. In many cases, you will have to be satisfied in recognizing the genus (the first word in the scientific name) or the group (e.g. shield lichens). Experts often use colour tests to be certain of the species. They drop a reagent on the thallus and look for a specific colour change.

On tree bark, the most obvious species are usually the foliose shield lichens like Common Greenshield (Flavoparmelia caperata). It has pale-green lobes with a black lower surface and resembles a thin, flat, leafy circle. A similar species is Hammered Shield Lichen (Parmelia sulcata). This foliose lichen has blue-gray lobes with a distinctive pattern of white cracks on the surface. It is pollution‑tolerant and easily found on the bark of city trees. A crustose species to look for is Dust Lichen (Lepraria lobificans). It is yellowish-green to pale mint in colour and resembles paint or dust on the bark. Common fruticose lichens include the various species of beard lichens (Usnea species). Bristly Beard (Usnea hirta) is very common on the branches of coniferous trees and birch. It has yellowish-green, densely branched, erect stems. Other species literally look like a beard hanging from a branch with hairs up to 40 cm in length. Many grow on spruce trees.

On rocks, watch for different rock tripes (Umbilicaria species), which are foliose lichens. They often resemble dark, leathery leathery lettuce leaves. Smooth Rock Tripe (Umbilicaria mammulata) grows on steep rock walls and boulders in forests. It has reddish-brown lobes and grows from a central stalk. The lower surface is pitch black. Cinder Lichen (Aspicilia cinera) is a common crustose species. It has an ashy-gray, cracked surface with multiple black spots. On limestone and limestone gravestones, you might come across other crustose lichens called firedots (Caloplaca species). Depending on the species, they are yellow or orange in colour. Sidewalk Firedot (Caloplaca feracissima) is common on limestone, including gravestones.

On ground substrate, you may come across the best known and most easily identifiable of all the lichens, namely British Soldiers (Cladonia cristatella). This fruticose species is named for its resemblance to the uniforms worn by English soldiers during the Revolutionary War. Look for greenish-grey stalks, topped with bright crimson red caps (the spore-producing apothecia). Another fruticose species, Trumpet Lichen (Cladonia fimbriata) often grows alongside British Soldiers. The grey-green thallus stands about 20mm tall with a distinctive trumpet or golf tee shape. Reindeer lichens (Cladina species), too, grow on the ground and belong to the fruticose group. They resemble tiny white, grey or greenish shrubs or coral with numerous branches. You can sometimes find three or four Cladina species in a single clump. Carpets of Cladina can cover huge areas. A common foliose genus, the pelt lichens (Peltigera species) have semi-erect, grey-green to brownish lobes and superficially resemble rock tripe.

Appreciation

Lichens are important in many ways. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds use shield lichens (Parmelia) to camouflage their nests; deer, moose, caribou and even flying squirrels eat lichens; and tree frogs take advantage of the camouflage lichens provide. Indigenous Peoples still use lichens as dyes for crafts and other artifacts.

By degrading rock surfaces and providing a site where organic material can collect, lichens are the primary colonizers of barren landscapes such as rocks. As the lichen grows, these processes speed up and occur over an ever‑expanding area. Eventually, mosses, grasses or ferns may take root in the modest accumulation of soil and replace the lichen.

The degree of lichen diversity in a given area is also a good “bio-indicator” of the amounts of certain pollutants in the air. Some lichens are especially sensitive to sulfur dioxide. Part of the reason for this intolerance is their extreme efficiency in accumulating chemicals (such as sulphur) from trace levels in the atmosphere. Sulphur destroys the chlorophyll in the algal cells, which inhibits photosynthesis and kills some lichens. It is therefore possible to estimate the amount of sulfur dioxide in the air by observing the number and type of lichens growing in an area.

An extreme example of a lichen’s ability to absorb matter from the atmosphere was seen in northern Scandinavia after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Reindeer lichen accumulated so much radioactivity that reindeer feeding on it were considered unfit for human consumption.

Maybe the most important reason to appreciate lichens, however, is for their beauty. Take time to look at them through a good 10x hand lens. A beautiful world will be revealed. My favourite is the colour contrast between the frosted green stalks and the red tips of the British Soldier lichen. Close-up photography, too, is very satisfying. Put your digital camera on a sturdy tripod and use the macro setting.

As for resources, I especially recommend “Lichens of the North Woods” by Joe Walewski. “Forest Plants of Central Ontario” also has a small section on common lichens. A great online resource is the lichens page of the USDA Forest Service website.