When it comes to seeing new species of plants and animals, a certain amount of effort is usually required. This might mean traveling to new locations and walking considerable distances. There is, however, a way to enjoy nature’s diversity that can appeal to even the most sedentary among us. Welcome to the gentle art of moth-watching. “Mothing” can be as simple as leaving the porch light on and checking periodically to see what is clinging to the screen door.

With 165,000 described species worldwide, moths are among the most diverse and successful organisms on Earth. Their colours and patterns range from bright and dazzling to so cryptic as to define the very idea of camouflage.

Let’s begin by distinguishing moths from butterflies. Butterflies have club-like knobs on the ends of their antennae and usually perch with their wings held upwards. Moths, on the other hand, tend to perch with their wings outspread and have antennae that closely resemble bird feathers. Both moths and butterflies make a protective covering for the pupal stage of development. Moths, however, make a cocoon, which is wrapped in a covering of silk, while butterflies make a chrysalis, which is hard, smooth and has no silk covering. Unlike their sun-loving cousins, most moths are nocturnal.

Local moths

Moths are common just about everywhere there are trees and shrubs. This makes the Kawarthas a veritable moth paradise. Over 1000 species have been identified in Peterborough County, but they are probably many more. Basil Conlin, a Trent University student, has observed 560 species on the Trent campus alone!

Different moth species fly at different times of year. The season begins in late March or April with sallow moths like “The Joker” (Feralia jocosa) and extends right into December when the autumnal moth (Epirrita autumnata) can be common. Late May, June and early July, however, is the most exciting time of year for “moth-ers”, since this is when the spectacular giant silkworm moths are on the wing. From the bright yellow of the Io, to the bold eye-like markings of the Polyphemus and the palm-size wingspan of the Cecropia, these moths are truly exceptional.

Giant silkworm moths take their collective name both from their impressive size and from the fine silk they use to spin their cocoons. (Note: Commercial silk comes from the silkworm moth, which belongs to a different family.) They can turn up just about anywhere and are most active on warm, still nights after 10 pm. One of the best places to look for them is on large buildings with bright lights that shine onto walls.

Probably the best known of our silk moths is the Cecropia. Its body is red with exquisite white bands around the abdomen. Each of the dark brown wings boasts a stunning red and white crescent spot. Cecropias ride the June breezes in search of romance. The females release tiny quantities ‑ literally billionths of a gram ‑ of airborne sexual attractants called pheromones. These are still sufficiently potent to attract males from great distances. The male’s large, feather‑like antennae are covered with sophisticated olfactory sensors that sift the sweet night air for the female’s scent. If the breeze is right, males can follow a female scent plume for several kilometres. When male and female finally meet, they join at the abdomen and remain attached for up to 24 hours. The female will then begin to deposit 100 or more eggs on the undersides of leaves of trees such as cherry, birch and maple. Adult silk moths exist for the sole purpose of reproduction; in fact, they have no mouthparts and don’t eat.

Another spectacular species to watch for is the Luna. Pale green in colour, its hindwings end in a long curving “tail”. Other relatively common silkworm moths in the Kawarthas include the Polyphemus, the Promethea and the Columbia.

Sphingids and Catacolas

A group that warrants special attention from spring through fall is the sphinx and hawk moths (sphingids). Sphingids are often brown or grey in colour, moderate to large in size, and have narrow wings and sleek abdomens. This makes them fast flyers. Many have an impressively long proboscis for feeding on nectar. Although most Sphingids are either nocturnal or crepuscular (active at dusk and dawn), some species fly during the day. These include the gallium sphinx and the hummingbird clearwing moth. Night-flying sphingids are often attracted to tube-shaped white flowers with a strong scent.

A few other sphingids to get to know are the one-eyed, elm and big poplar sphinxes. The latter has a wingspan that reaches 12 centimetres and, when at rest, it resembles a fighter jet!

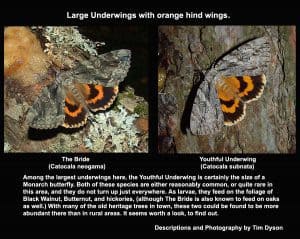

Moth-ers also look forward to mid-summer when the underwing (Catocala) moths start flying. Unassuming at first glance, they are called underwings because of the remarkable contrast between the nondescript forewings and the bright, colourful hindwings (underwings). In many species, the underwings are boldly marked with black bands on an orange or yellow background. When the forewings close, however, the insect effectively “disappears.” Some common local species include the pink, scarlet, once-married and sweetheart underwings.

Moth identification

To identify moths, start by focusing on the larger species and those that stand out from the rest because of their distinctive colours or markings. Pay special attention to how the moth holds its wings when at rest. Are the wings spread out to the side or tent-like over its back? A moth with tent-like wings probably belongs to the Noctuidae family. Once you have an idea of what family the moth might belong to, look more closely at the patterns on the wings and try to compare these to the photographs on a website or in a field guide. I would recommend purchasing the new Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America by Canadians David Beadle and Seabrooke Leckie.

The guide shows you the time(s) of year each moth flies as well as its geographic range. It also gives you the host plant(s) the moth requires. If, for example, a given species lays its eggs on oaks and they are plentiful in your area, this is important information. Two excellent moth websites for identification purposes are BugGuide at www.bugguide.net and the Moth Photographers Group at http://mothphotographersgroup.msstate.edu/ You can also view local moth sightings by going to my website at drewmonkman.com Go to the topics page and scroll down to “Moths”.

Attracting moths

To bring moths to you, purchase a bulb that projects light in the UV spectrum such as a black light CFL. Screw the bulb into a lamp – a floor lamp works well – and place in front of a white sheet. The moths will land on the sheet, making them easy to see.

Not all moths, however, are interested in lights. Some are nectar-feeders and will come to a sugary bait. Mix together an over-ripe banana, a dollop of molasses, a scoop of brown sugar and a glug or two of beer. Spread the concoction on a tree trunk or hanging rope and check regularly to see what shows up. This is a great way to attract underwing moths.

A lot of the fun in mothing comes from photographing and identifying the insects. Be aware, however, that a flash can sometimes create washed-out images. A way to get around this problem is to carefully catch the moth in a small container and put it in the fridge overnight. You can then take a picture of it the following morning using natural light and a pleasing background such as a leaf or piece of bark. You may also wish to place a ruler beside the moth (a useful size reference) for one of the shots. You’ll only have about 30 seconds, however, before the moth warms up and flies away.

Moth atlas

Unlike birds and mammals, there are still large gaps in our knowledge of Ontario’s moths. It is for this reason that the Toronto Entomologists’ Association (TEA) recently launched the Ontario Silk Moth and Sphinx Moth Atlas to gather data on their distribution, abundance and seasonal patterns. The TEA is asking people to contribute photo records of silk and sphinx moth sightings, including those needing an ID, to inaturalist.ca/projects/moths-of-ontario. The atlas already contains about 4,200 silk observations -many of them from older databases. It can be seen online at ontarioinsects.org/moth/. The hope is that the moth atlas will evolve into a rich dataset like the Ontario Butterfly Atlas, which can be seen at ontarioinsects.org/atlas.

Researchers are seeing a disturbing decline in silkworm and sphinx moth populations across northeastern North America. This has been especially notable in species like the io moth and great ash sphinx. A possible cause is Compsilura concinnata, a tachnid fly that was introduced from Europe to control gypsy moth populations. The fly is known to also attack native moth species like giant silkworm moths.

Peterborough Field Naturalists event

On June 10, Basil Conlin and the Peterborough Field Naturalists will be holding an evening of mothing at the Camp Kawartha Environment Centre, starting at 8:30 pm. The Centre is located at 2505 Pioneer Road. Basil will give a talk on moth identification, as well as methods for attracting, collecting and observing moths. In addition, participants will be able to sit and watch moths coming to a light sheet and to bait. Bring boots, a flashlight/headlamp and maybe a blanket and snacks. The evening will wrap up by 11:30.