The lovely spring weather we’ve enjoyed this past week has caused an explosion of plant growth. Buds are swelling, grass is turning green, and a half-dozen species of wildflowers are in bloom. The blossoms are already attracting the first bees. Although I’ve witnessed this rebirth of nature over too many springs to count, the wonder of flowers and their pollinators never ceases to amaze. What better way to celebrate Earth Day than to take some time to understand and appreciate the extraordinary story of pollination and to think about what you can do to welcome pollinators to your garden or balcony.

To human eyes, flowers embody beauty and vitality. We rave about the colours, the shapes, the symmetry and, of course, the intoxicating scents. It’s therefore tend to forget that human beings are not the target audience for these alluring plant structures. Flowers have evolved for one thing only: to produce seeds and thereby assure another generation. The mechanism by which this occurs – pollination – is one of nature’s most fascinating phenomena and a crowning achievement of evolution. Yet, the beauty, intricacy and importance of pollination is often taken for granted, as is the role played by a host of pollinator species, many of which are in serious decline.

What is pollination?

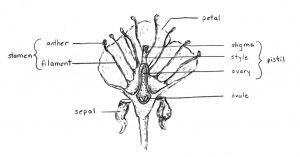

To understand pollination, we need to reacquaint ourselves with the parts of a flower (see diagram). As with human beings, some flowers are either male or female. Separate male and female blossoms can be on the same plant – most often a tree or shrub – or on separate plants. A willow tree, for example, is either male or female, with only the female trees producing seed. Other flowers , known as “perfect” (like the one in the illustration), have both female and male structures. The latter produce pollen, which is the source of male sex cells and analogous to sperm in animals. Pollen production takes place in the anther at the top of the male flower part known as the stamen. The eggs (ovules), or female sex cells, are located in the ovary at the bottom of the pistil, the flower’s female part. At the top of the pistil, there is a sticky surface called the stigma – think of “stickma”. Pollination occurs when pollen grains are transported by the wind or on the body of an animal from the anther of one flower to the stigma of another flower of the same species.

The second step in the pollination process is fertilization. A flower becomes fertilized when a pollen grain on the stigma grows a pollen tube, which makes its way down through the style and into the ovary. Inside the pollen grain, male sex cells are then produced. These cells travel down the tube and fertilize the ovules. The fertilized ovules grow into seeds, and the ovary wall becomes the encasing fruit around the seeds. The next time you bite into an apple, take a moment to reflect that you are actually eating an apple flower’s ovary! Similarly, a milkweed pod is simply a ripened ovary containing seeds.

An analogous process occurs in conifers. Male cones – the small, delicate ones that litter the ground in late spring – produce pollen. They are yellowish when ripe, because of the pollen dust they contain. The pollen grains are carried by the wind and, by dint of their astronomic numbers, some come into contact with female cones. These are the familiar woody “pine cones” and contain ovules. The ovules are located under plate-like scales. The scales open temporarily in the spring to receive the pollen. They then close during fertilization and maturation. The scales re-open again at maturity to allow the seed to escape. Depending on the species, seed maturation takes 6–8 months in conifers such as spruce but from 18 – 24 months in most pines. Female cones are quite different in size and shape from one kind of conifer to the next.

Pollinators

Plants that rely on wind to move their male sex cells have light and dusty pollen. The male flowers often hang loosely and sway back in forth in the wind, which helps to release the pollen. Some, like those of poplars, oaks and birches, look like soft caterpillars hanging down from the stems. In most cases, these flowers lack petals, are dull in colour, and have no fragrance. There’s no need for the plant to invest in petals, bright colours and alluring scents since there’s no need to attract pollinators. Wind-pollinated flowers usually appear before the leaves come out, since evolution has “learned” that leaves would get in the way of effective pollen transfer.

A great many plants, however, depend on insects to transport their pollen, although hummingbirds and bats sometimes do the job. Collectively, these animals are known as pollinators. They visit flowers in search of food, which can be nectar or the protein-rich pollen itself. Bees intentionally collect both pollen and nectar. They feed the pollen to their developing offspring. Butterflies, moths and hummingbirds, on the other hand, feed only on the nectar. Markings in the flower sometimes guide the pollinator to the nectaries where the sweet liquid is located. As they feed, the pollinators brush up against the stamens and pollen inadvertently adheres to their body. Then, when they move on to another flower, the pollen is accidentally transferred to the sticky top of the pistil. Animal-pollinated plants produce pollen, which is too heavy to be moved very far by the wind. This is why goldenrod pollen is not the cause of hay fever. Rather, the light, wind-borne pollen of ragweed is the culprit.

Evolution

Flowers have evolved in remarkable ways to attract pollinators, which in turn have evolved in response to changes in the plants. In other words, each organism has developed adaptations, which work to its own benefit. For instance, flower evolution has produced an amazing array of colors, markings, shapes, fragrances and even different flavours of nectar. Some plants like skunk cabbage even go further. Skunk cabbage could almost be described as “warm blooded” because they generate heat. The warmth, along with the plant’s putrid smell, attracts early spring insects, which are looking for food and a spot to warm up. In exchange, the insects end up accidently pollinating the plant.

The flower-pollinator relationship is especially interesting when it comes to bees. Many species are attracted to the colours blue and yellow, to bilateral symmetry (e.g., the shape of a daisy) and to flowers with lines leading to the nectar. Consequently, over millions of years, many plant species have evolved these characteristics in order to attract bees. The bees, in turn, inadvertently distribute the plant’s pollen grains and optimize its reproductive success. It doesn’t stop there, however. Simultaneously, the plants have exerted pressure on the bees by favoring behavioural and structural traits that allow these insects to take advantage of the nutritional rewards offered by the plant. Hairiness is one such trait. Hairs all over the bee’s body actually have a strong positive charge with attract the negatively-charged pollen grains. This kind of relationship is known as co-evolution.

Richard Feynman, a famous American physicist, had an artist friend who said that a scientist can’t appreciate the beauty of a flower the way an artist can. His artist friend felt that by studying a flower scientifically and ‘taking it all apart’, the flower loses its beauty. Feynman disagreed. He said that, as a scientist, he sees more beauty and wonder in a flower – not less – than even the most sensitive artist sees. Scientists can imagine the cells, the complicated actions going on inside, and the fact that the colors evolved in order to attract insects to pollinate the flower. In other words, scientific knowledge only adds to the excitement, the mystery and the awe of a flower. The more you understand the biology of plants and pollinators, the more your appreciation grows, starting in your own garden.

Peterborough Pollinators

How do we empower citizens to protect pollinators and, in doing so, create, restore and celebrate natural environments in the Peterborough area? A group of local citizens has set out to answer this question. Peterborough Pollinators is working to encourage the creation of pollinator gardens throughout the city. Not only will these gardens help pollinators, but they will also bring greater food security, sense of place and community development to our neighbourhoods and daily lives.

We’ve all heard about the mysterious decline of honey bees. However, other bee species are also declining, largely because of habitat loss. You can make a big difference just by creating a bee- and butterfly-friendly space in your garden. To learn more about Peterborough Pollinators, take part in upcoming workshops, access resources and sign up for their newsletter, visit peterboroughpollinators.com Resource information is also available at peterboroughdialogues.media/pollinators/